History was a subject I enjoyed…I studied history at Purdue, graduated, and tried teaching for a year. My short tenure had nothing to do with the subject and everything to do with the classroom. I felt cooped up, and I didn’t relish the thought of spending a career sitting in a room for the next 40 years. I left teaching and pursued a different career that released me from that one static location and provided the variety my psyche needed.

I left the classroom, but I didn’t leave history. I continued to learn. I read it, listened to it in conversations with my grandparents and others of their generation. I saw it in the places I traveled, and I found it in old homes, barns, museum archives, and along the roads I’ve traveled. What were the stories that belonged to the names on the old tombstones?

Over time I noticed the history we’ve been given doesn’t always match the history that was—especially when it comes to heroes.

That brings me to James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me, especially that first chapter—“Handicapped by History: The Process of Hero-making.” He lays out how we sanitize, simplify, and mythologize historical figures—turning complex, flawed people into marble saints.

Loewen argues that by teaching a “feel-good” version of history, we deny students the truth about their country’s past and rob them of the chance to see how real change happens. He asks a key question: Why do we need our heroes to be perfect?

As Americans, we love our legends—our brave frontiersmen, our fearless generals, our trailblazing presidents, winning sports figures, or business tycoons. But many of the names we learned as children start to look different when viewed from another angle.

William Henry Harrison was a name I heard with pride growing up in Indiana, but the older I get, the more I admire the man he fought: Tecumseh. One built his name expanding American territory; the other died trying to preserve a homeland. It makes you wonder who gets to be a hero—and who gets forgotten.

Heroes have their names on schools, parks, bridges, and monuments. We carve their faces onto mountains and mint them onto coins.

This begs the question: What is a hero—and more importantly, who gets to decide? Most definitions of a hero include the attributes of courage, sacrifice, and integrity. Someone who acted selflessly in the face of danger or injustice. Sadly, in practice, definitions tend to become murky. Sometimes we elevate people because they were first, or loudest, or happened to be in the right place at the right time.

True heroism rarely seeks attention. More often, it is quiet. Sometimes it is forgotten. Other times it was never recognized in the first place.

Loewen suggests we need to understand how we elevate the powerful and erase dissenters. Accepting a single version of history—one that flatters the dominant narrative instead of challenging it—leads us to misunderstand not only our past, but ourselves, our country, and the shape of the future we’re creating. We ignore the complexity of our history at our own peril.

If we want a healthy democracy, we must be willing to challenge our stories, to seek out the complete story. Without that effort, we don’t have citizenship—we have spectators.

We have heroes of all kinds. Some fit the definition—or maybe they are the definition. Others are heroes in name only. Widely recognized names that have been glossed over, cleaned up. To be fair, some of those exhibited both heroic behavior and anti-heroic behavior. Humans are complicated, and history is often taught from only one side, cheating us out of the full story.

Heroes come in at least three varieties.

The Genuine and Unknown: Those who never made it into the history books are the largest of the three groups. They were on the front lines of labor and civil rights. Like the unnamed nurses of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, they all fit the definition of hero. The whistleblower, the quiet legislator who casts the right vote knowing it’ll cost them politically. There are more—many more. Their courage didn’t come with fame or applause, and they deserve more than a footnote in someone else’s myth.

The Genuine and Well-Known: Not more deserving than the unknown heroes that surround us, but their names and deeds have had more exposure. Their stories were performed in public view and are easier to see and to tell—unlike the unseen, unglamorous work of those behind the scenes. Stories that fit the Hollywood mold are easier, safer, and more popular. And in large part, the difference depends on who writes the story.

Let’s look at a few of those genuine and well-known heroes, and some of the reasons we think of them as heroes.

John Glenn: His life exhibited courage, service, integrity, and humility. Not only was he a space pioneer, but during World War II and Korea he flew 150 combat missions. He wasn’t just brave in theory—Glenn willingly faced danger long before his name became a household one. After leaving NASA, he served 24 years as a U.S. Senator and was known for integrity and thoughtful governance.

Well-known heroes come from all walks of life, from all occupations—or no occupation at all. Consider this: In the early 20th century, polio was one of the most feared diseases in the world. Dr. Jonas Salk led a team that developed the first safe and effective vaccine in 1955, improving public health forever. Even more heroic, the doctor refused to patent the vaccine. When asked why, his response was: “There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?” He might have become enormously wealthy. Instead, he chose to make the vaccine available to all. That doesn’t sound much like a modern pharmaceutical company talking point to me.

Sometimes heroes are seen as groups, not individuals. Consider the firefighters who ran into the Twin Towers when everyone else ran out. Remembering them as a group makes the individuals no less heroic.

Not all heroes are without fault. Two of the most often listed American heroes are George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. Both exhibited personal and leadership flaws. We all remember the reasons they are thought of as heroic and mythic, but those stories often gloss over the flaws. Yet, their inclusion as true heroes is still valid in the way they displayed courage in crisis and restraint with power.

We know what heroism looks like on a movie screen—bombs exploding, soldiers sprinting into danger. But real heroism? It doesn’t always come with music or medals. Sometimes it’s quieter, slower, and doesn’t make the highlight reel.

History books are full of heroes. Many with that designation have lost that title upon closer examination of their lives. Let’s look at a few of those.

OJ Simpson: Athletic hero, brought down by violence, manipulation, and celebrity spectacle.

Christopher Columbus: A history book favorite who lost that status upon a closer look and better understanding of his actions, including slavery, violence, and exploitation of Indigenous peoples.

Lance Armstrong: Overcame cancer and won seven Tour de France titles, later falling from grace due to his involvement in a sophisticated doping scheme.

Joseph McCarthy: Hailed as a patriotic protector of American values—until he went too far and even his supporters backed away. Yet echoes of his tactics remain.

Richard Nixon: Twice elected and admired for diplomatic achievements, but his presidency collapsed under the weight of Watergate and the abuse of power that forced his resignation.

Image without integrity can make for short status as hero. It doesn’t take much for the shine to wear off. And yet, some figures cloaked in wealth and power seem to keep their status no matter how close we look.

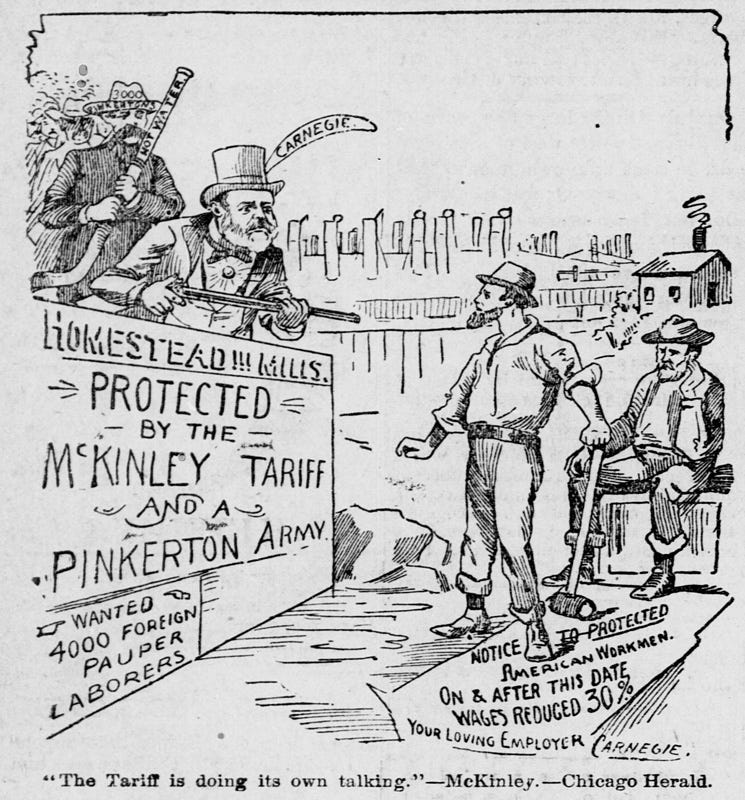

Wealth has a way of editing history. Two great examples are John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie.

Rockefeller is remembered today for founding the University of Chicago and funding medical research. He is less remembered for the Ludlow Massacre, where striking miners and their families were murdered under pressure from Rockefeller-owned coal companies.

Andrew Carnegie gave away millions, but controlled a steel empire that violently crushed the Homestead Strike with hired Pinkerton agents. Were they true philanthropists—or did they use their wealth more as a cover than a cure? You be the judge.

Massive wealth brings the power to tell your own story—true or not.

And that’s what makes this moment in our nation’s history so dangerous. As we accelerate toward oligarchy, we’d do well to stop asking only what stories are being told—and start asking who is telling them. Who benefits from these myths? Who gets remembered, and who gets erased?

Because when history becomes a product of wealth, truth is no longer the author.

And democracy doesn’t stand a chance when money writes the last word.

As always, thank you!

I am part-way through "Myth America" (Historians Take On the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past, By Kevin M. Kruse, Julian E. Zelizer, 2023)

Great. And we have to look outside the usual villainized treasure chests for money’s influence. Sometimes it’s lucrative book sales for the author or publisher exposing the scandal of “_____.”