Invasive Plants and the People Who Love (or Ignore) Them

As we move into summer, I’m spending more time fine-tuning my landscaping. May was wetter than usual—at least that’s how it felt to me. I managed to get most of the annuals planted, and as usual, I’m fighting what feels like an unending battle against plants I don’t want to be part of my landscape. Plants that don’t belong here.

Some of them I inherited when we bought the house (I should’ve paid closer attention). Some are unwanted gifts from neighbors (I wish they’d do better about attacking those plants from their side of the fence). Others are dropped off by our friendly neighborhood birds, who eat but don’t digest some seeds. (I suppose they can’t help it—when you have to poop, location doesn’t matter much if you’re a bird.)

What I’m talking about are those plants we label “invasive.” Most aren’t native to Indiana—or even to the U.S. Others are native but, once they go rogue, they lose all sense of place and purpose. Like all pathological villains, they have no morals and no regrets. They spread chaos, terrorize the delicate and desired, and taunt the hard-working guys like me armed with hoes, clippers, and Roundup. Their utter disregard for my time is getting personal. Anyone got a flamethrower?

“Invasive” sounds like the kind of word a politician uses when they don’t want to offend anyone. These plants aren’t just invasive—they’re botanical bully terrorists, hellbent on domination. They don’t knock. They don’t ask. Sometimes they sneak in. Other times they’re invited—by well-meaning gardeners who don’t yet know what kind of trouble they’re unleashing. They start off looking like guests, then choke your perennials, smother your shrubs, and swallow your fence while you’re admiring their flowers. You will regret your hospitality.

I understand why people plant them—sort of. But what they don’t think about is where those plants (or their offspring) will go next—or what nightmares they’re handing off to their neighbors. I might be exaggerating, but I honestly believe some of these bullies could eat your house if you let them. If you plant them and walk away, you’re not just landscaping—you’re launching a ground war.

A Word About the Environment

I’m not trying to wade into every environmental controversy out there, but I do want to focus on this one piece that hits close to home—literally. It helps to start with a simple idea: the environment is the place where plants, animals, and people live—ideally, in some kind of balance.

Natural environments are fragile. They rely on that balance, where every part plays a role. When one piece gets damaged, disappears, or bulldozes everything around it, the whole system suffers. And sometimes, even the things we humans find annoying, dangerous, or ugly—like poison ivy—serve a valuable purpose. They belong in the system. They fill a need.

Now, here I am complaining about invasive species, when I’ve made plenty of changes to my own yard—introduced plants, removed others, carved out flower beds. So yeah, maybe it sounds like I’m being a little hypocritical. But here’s the difference: I’m trying to be a responsible neighbor in the ecosystem. These invasives don’t just bend the rules—they break the whole system. They don’t adapt. They take over.

The Usual Suspects

The Indiana DNR has identified more than 40 invasive plant species as harmful to our native environment. I don’t think they rank them, but I do. Here are my top five personal offenders—based on sheer back pain, stubbornness, and ecological arrogance.

WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE

1. Asian Bush Honeysuckle

Public Enemy Number One. It’s not even that attractive, and yet it’s everywhere. Introduced to Indiana in 1897 (bad idea, folks), it quickly escaped and now forms dense thickets up to 20 feet tall. These thickets crowd out native plants, block sunlight, prevent tree seedlings from growing, and leave nothing but bare soil behind. That leads to erosion and a full-on collapse of plant diversity. The birds eat the berries, but they don’t get the nutrition they need—and then they scatter the seeds like confetti at a parade.

None of this is theoretical. Just take a walk along the Wabash Trail or drive down almost any Indiana highway—you’ll see it. And you won’t see the native plants that used to thrive there. I’ve spent the last three days clearing out a thicket that invaded from next door. The landlord? Not interested. But that’s a rant for another day.

2. English Ivy

A vine with a charming accent and a criminal record. It looks good crawling up old brick walls—until you realize it’s also burrowing into wood, stucco, mortar, and maybe your retirement fund. It’s a maintenance nightmare. If you’ve ever tried to remove it from a house or fence, you know it clings like a desperate ex. It doesn’t just damage buildings—it smothers trees, kills off understory plants, and turns your flower beds into no-go zones.

This one was here when we moved in. I’ve learned to stay ruthless. Gardening should be satisfying—not a hostage situation.

3. Bradford Pear

This one’s a story of good intentions gone sour. The USDA introduced it in the 1960s as a decorative tree, and people fell in love with its blooms. But it didn’t take long for its flaws to show. It smells bad, breaks easily, spreads everywhere, and forms dense thickets in natural areas. You don’t even notice them—until spring, when they all bloom at once like an uninvited high school reunion. Oops.

4. Chickweed

Sounds gentle, doesn’t it? Like a garnish or a nickname for a backyard chicken. But down on your knees in the garden, pulling out this stubborn little menace by the fistful, you won’t find it so charming. It forms dense mats, steals water and nutrients, and gives safe harbor to insect pests and disease. There’s no easy way to eliminate it short of napalming the yard—and I’m not quite there. Yet.

Sure, it’s edible. Some even claim it has medicinal uses. Personally, I’d rather it just not strangle my begonias.

5. Burning Bush

This one stung a little. We had a beautiful, mature burning bush by the front walk. Come fall, it would light up like a bonfire, and I’ll admit—it was hard to let it go. But once I learned and saw myself what it was doing to our woods and fields, I couldn’t keep making excuses.

Burning bush spreads aggressively, forms thick root systems, and even after cutting it down, sends up new shoots like a plant possessed. It’s been illegal to sell or transport in Indiana since 2020. When the DNR offered native replacements, I fired up the chainsaw. It was time.

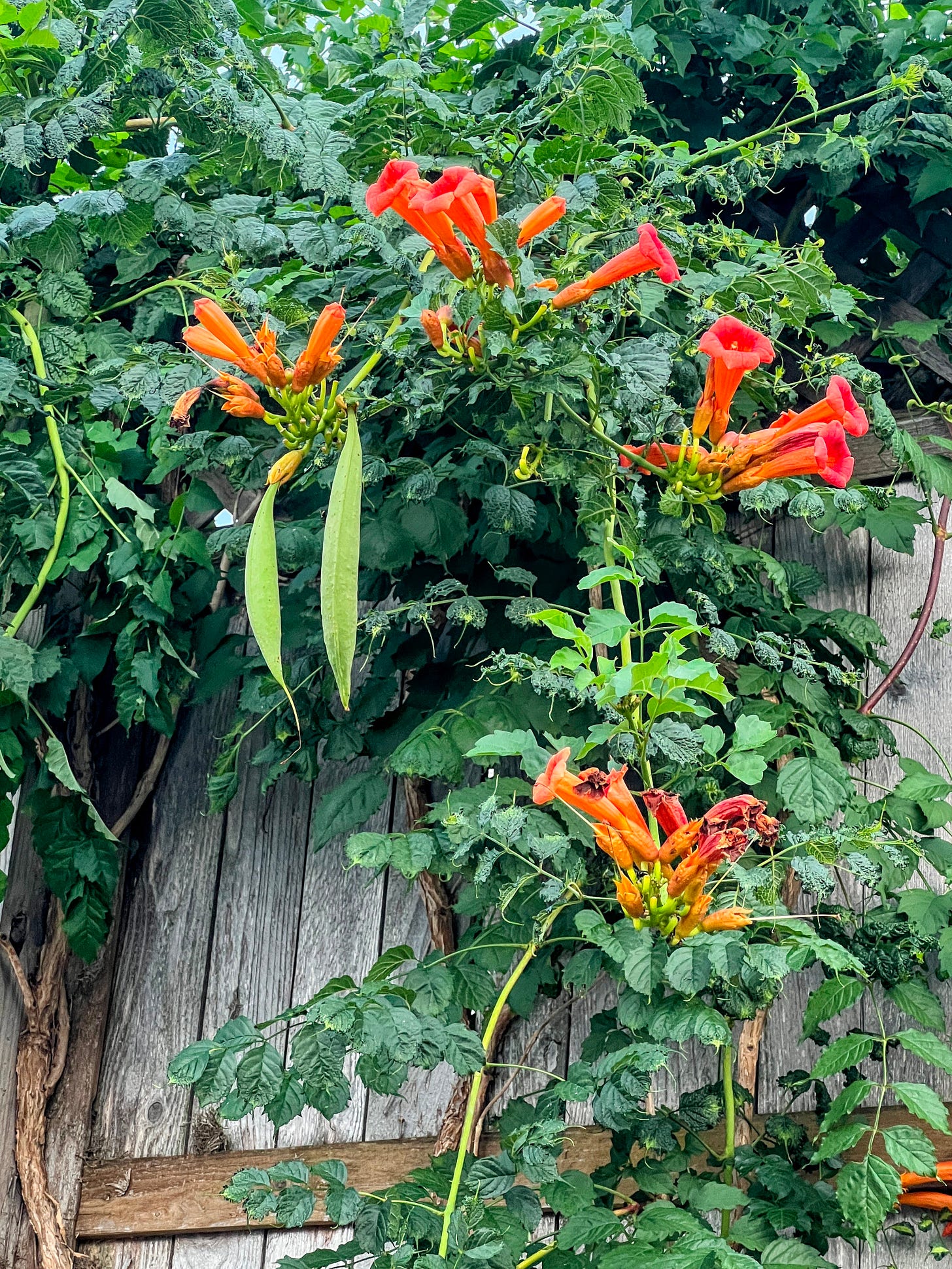

Not all problem plants are classified as invasive, even though they act much like they want to invade. Native trumpet vine is a good example. It is native to the eastern half of the country and it does have a couple of outstanding traits. Hummingbirds love the brilliant orange flowers. However, if you are thinking about planting it, be careful and plan on working regularly to prevent it from going everywhere. Milkweed is another example…it’s a native here, it has nice summer blossoms and it attracts and benefits Monarch Butterflies but if you are not careful it will spread aggressively.

Final Thought

If you’ve made it this far, you’re either a fellow gardener, a curious neighbor, or someone who suspects their shrubs might be plotting against them. Invasive plants aren’t just a nuisance—they’re a threat to the places we call home.

We can’t fix the whole environment overnight. But we can start in our own backyards.

IS IT JUST ME Will always be available as a free subscription. However, You may choose to be an important part of bringing more of these sorts of stories to the playground. To support my storytelling work and provide a bit of motive please consider becoming a paid subscriber. If you don’t yet see the value, please become a free subscriber to receive notifications each time I post new content. Please share if you find something worthwhile. As always I enccourage and welcome comments and please share. Thanks for joining me today.

I do in fact have a "flamethrower." Flame weeder, it is officially called, and it is the "Red Dragon" brand. I used it attached to a 2.4 gal propane tank (like on millions of outside propane grills). It has not been out of the barn for five years unless India has used it, but if you're interested let me know. (Something makes me think you're not really inclined to take a flame weeder to anything so close to your home or shed.)